Diesel engines have been around for more than half a century. Chances are that if you are around fleets or equipment, you have encountered a diesel engine. They have been described as the workhorses of the industry, and they provide users across industries with the power they need. Whether it’s in the form of a generator for a medical facility, a tractor engine on a farm or an engine on a school bus, diesel engines are everywhere.

Diesel engines have evolved, and a diesel engine today may not exactly line up with the diesel engines of the past. However, their evolution has been slower than that of the gasoline engine. For instance, many diesel engines today still use a 40-weight oil (albeit multigrade or semi-synthetic) which can tell us about the changes in the viscosity requirements over the years.

This column explores how the specifications changed to get a better idea of:

- The evolution of diesel engine oils

- Some reasons behind its degradation

- Ways that degradation sources can be identified through oil analysis

Understanding Diesel Engine Oil Specifications

As per the American Petroleum Institute (API), the standards governing Diesel Engine oils began with the CA spec which became obsolete in 1959. The latest diesel engine oil standards were upgraded to CK4 and FA4 in December 2016. On the other hand, the gasoline spec entered its latest standard, the SP spec which includes 0w16 and 5w16, in May 2020.

What Does This Mean for Your Fleet?

Most API standards are backward compatible. This means that an engine that requires a CJ4 spec oil can still use a CK4 spec oil, but the reverse is not true.

For more modern engines, oils have been engineered following environmental regulations that did not exist 50 years ago. Additionally, these newer engines now have more demand compared to older engines.

As such, the oil is under more duress and must perform under these conditions. Newer oils are formulated with this in mind.

CK4 oils provide enhanced protection against oil oxidation and viscosity loss caused by shear and oil aeration, catalyst poisoning, particulate filter blocking, engine wear, piston deposits, degradation of low- and high-temperature properties, and soot-related viscosity increase compared to the CJ4 oils (API, 2024). It must be noted that FA4 oils are not backward compatible with the CJ4 oils nor are they intended for on- or off-highway applications which require CJ4 oils.

The FA4 oils are blended to a high-temperature, high-shear (HTHS) viscosity range of 2.9 centipoise (cP) to 3.2 cP to assist in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. They are especially effective at sustaining emission control system durability where particulate filters and other advanced aftertreatment systems are used.

These oils also provide enhanced protection against oil oxidation and viscosity loss caused by shear and oil aeration. In addition, they protect against catalyst poisoning, particulate filter blocking, engine wear, piston deposits, degradation of low and high-temperature properties, and soot-related viscosity increase.

What’s the Difference Between CK4 & FA4 oils?

CK4 oils are specifically designed for use in high-speed, four-stroke-cycle diesel engines designed to meet the 2017 model year, on-highway and tier 4, non-road exhaust emission standards and for previous model year diesel engines. However, these are also formulated for diesel engines using diesel fuel ranging in sulfur content up to 500 parts per million (ppm) (0.05% by weight). Diesel fuels that contain more than 15 ppm (0.0015%) may impact the exhaust aftertreatment system’s durability and/or the oil drain interval.

On the other hand, FA4 oils are xW30 oils specifically designed for use in select high-speed, four-stroke-cycle diesel engines designed to meet 2017 model year, on-highway greenhouse gas emission standards. These are particularly formulated for diesel fuels with a sulfur content up to 15 ppm (0.0015% by weight).

API FA-4 oils are not interchangeable or backward compatible with API CK-4, CJ-4, CI-4, CI-4+ and CH-4 oils. Additionally, these oils cannot be used with diesel fuel containing between 500 ppm to 15 ppm of sulfur.

Figure 1 shows the API donut for both specifications as detailed by (API, 2016). This API donut typically appears on every diesel engine oil that is sold (those that are original and not counterfeit).

Figure 1. API donutAmerican Petroleum Institute

Figure 1. API donutAmerican Petroleum Institute

Why Does My Diesel Engine Oil Degrade?

All oils degrade over time. They can be considered consumable items as they must be replaced over time. Diesel engine oils are no different except that they may be susceptible to certain mechanisms that turbine oils are not. The diesel engine is often placed under a lot of pressure to deliver power while keeping cool and managing emissions.

The critical areas for lubricant performance in a diesel engine usually include:

- Viscosity control

- Alkalinity retention, base number (BN)

- Engine cleanliness control

- Insoluble control

- Wear protection

- Oxidation stability

- Nitration

Typically, these factors are monitored in these types of oils to ensure that they remain in a healthy condition.

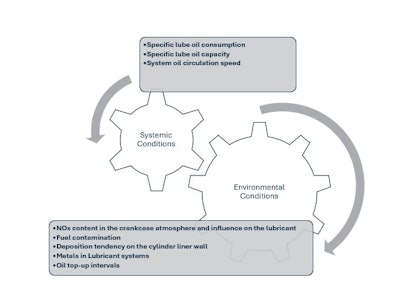

Several factors affect oil degradation in a diesel engine. According to The International Council on Combustion Engines (The International Council on Combustion Engines, 2004), these include specific lube oil consumption; specific lube oil capacity; system oil circulation speed; NOx content in the crankcase atmosphere; and influence on the lubricant, fuel contamination in trunk piston engines, deposition tendency on the cylinder liner wall, metals in lubricant systems, and oil top-up intervals. These can further be divided into systemic conditions (which cannot be easily altered) and environmental conditions (because of processes occurring within or to the system) as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Systemic and environmental conditions affect the degradation of diesel engine oil.Strategic Reliability Solutions

Figure 2. Systemic and environmental conditions affect the degradation of diesel engine oil.Strategic Reliability Solutions

Systemic Conditions

While lubricant degradation can be caused by environmental strains being placed on the lubricant, there are times when the operating design of the system also encourages degradation. Three such cases for diesel engine oils are specific lube oil consumption, specific lube oil capacity and system oil circulation speed.

Specific lube oil consumption (SLOC, g/kWh) is defined as the oil consumption in grams per hour per unit of output in kilowatts (kW) of the engine (The International Council on Combustion Engines, 2004). Over the years, there has been a reduction in the SLOC for engines with special rings inset into the upper part of the cylinder liner. These reduce the rubbing of the crown land against the cylinder liner surface.

With reduced oil consumption, oil top-ups, which would have introduced fresh oil into the system, are consequently reduced. This fresh oil would have increased the presence of additives and helped in maintaining the required viscosity of the current oil. However, since the SLOC is reduced, the oil does not get a “boost” during its lifespan and will continue to degrade at its current rate. Hence, a lower SLOC may encourage the degradation of diesel engine oil.

Specific lube oil capacity, also known as the sump size, which is the nominal quantity in kilograms (kg) of lubricant circulated in the engine per unit of output in kW. According to The International Council on Combustion Engines, the specific oil capacity does not directly affect the equilibrium level of degradation. However, it can influence the rate at which deterioration occurs as smaller sump sizes can increase the rate at which degradation achieves an equilibrium level. Typically for dry sump designs, the specific oil capacity is around 0.5 kg/kW to 1.5 kg/kW. These values are closer to 0.1 kg/kW to 1.0 kg/kW for wet sumps.

System oil circulation speed refers to the time taken for one circulation of the total bulk oil. In diesel engines, lubricants are usually subjected to blow-by gas (including soot and NOx) during their time in the crankcase. If the lubricant spends a longer time in the crankcase, it can become degraded at a faster rate. Typically, the time required for one circulation of bulk oil averages between 1.5 minutes to 6 minutes. However, we have seen the trend toward smaller sump sizes and, by extension, shorter circulation times, which should reduce the degradation rate.

Environmental Conditions

The environmental conditions that lubricants must endure can also influence their degradation. These conditions can either be enforced through the system, its operating conditions or from conditions outside the system. There are a few environmental conditions which must be addressed (The International Council on Combustion Engines, 2004).

NOx content in the crankcase atmosphere and influence on the lubricant has more applicability to gasoline engines compared to diesel engines but they should not be fully ruled out. Diesel engines are more susceptible to sulfur-derived acids (caused by the burning of diesel fuel). However, NOx can be produced by the oxidation of atmospheric nitrogen during combustion, which can affect degradation.

Field studies show a correlation between nitration levels, an increase in viscosity and an increase in acid in the oil. NOx can also behave as a precursor and catalyst that promotes oxidation through the formation of free radicals in the lubricant. On the other hand, there can be direct nitration of the lubricant and its oxidation products to produce soluble nitrates and nitro compounds. These can eventually polymerize to form similar by-products of oxidation. This can lead to increased acidity (lowering the BN) and increased viscosity of the lubricant.

Fuel contamination in trunk piston engines happens quite often in diesel engines. If the fuel injectors are defective or the seals do not effectively seal to keep fuel out, fuel enters the oil. When fuel is in the oil, oil can become degraded quickly, often causing the viscosity to reduce to a value that compromises the ability of the oil to form a protective layer inside the component. The fuel dilution test can quantify the content of fuel in the oil. Depending on the type of engine, the tolerance levels will differ.

Deposition tendency on the cylinder liner wall is usually caused by unburnt fuel or excess oil in this area or the chamber. Typically, the piston rings scrape these deposits back into the oil, leading to an increase in the volume of insolubles. This also increases the viscosity of the oil, and it appears a darker color.

Reducing the SLOC also decreases the deposits on the liner wall because special rings (near the top of the liner) are installed to have controlled clearance of the piston crown. This reduces the crown land deposit which can also minimize bore polish and hot carbon wiping.

In addition, with a reduction in SLOC, the number of oil top ups is also reduced. As such, the replenishment rate of additives (in particular the BN) is not as frequent. Therefore, the degradation of the oil will advance at a slightly faster rate due to the lower SLOC which affects the rate of top up.

Metals in lubricant systems can also act as a catalyst for the degradation of the oil. During the oxidation process, copper is one of the most common catalysts in addition to other wear metals (such as iron) which can increase the rates of oxidation. As such, the presence of these metals increases the degradation rate as well.

Oil top-up intervals must be managed in such a way that it does not disturb the balance of the system. Typically, when the sump level falls below 90% to 95% (depending on the manufacturer), a top-up is needed. When fresh oil enters the system, it replenishes some additives and breathes new life into the oil. However, with this change in temperature of new oil coming into the system (especially in large quantities of about 15%), the deposits held in suspension tend to precipitate.

Additionally, foaming (caused by the increased concentration of some additives) can occur if too much fresh oil is added at once. As such, oil top-up intervals must be managed to avoid further degradation.

Understanding Your Oil Analysis Results

Having the information above is great to understand how your diesel engine oil degrades, but how will you know that it is degrading? One of the most reputable ways is to submit your oil for testing in the lab. Depending on the type of diesel engine (on-highway, marine or off-highway), different tests will be involved. However, here are the basic ones that you should be familiar with.

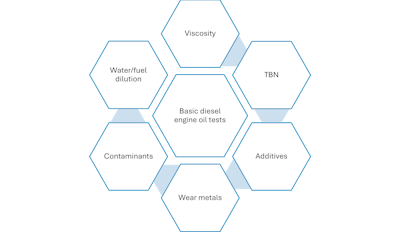

When determining the health of your diesel engine oil, the first thing to check is the oil’s viscosity, total base number (TBN), whether all the additives are at the correct levels, if there are any wear metals or contaminants present and finally the presence of water or fuel dilution as shown in Figure 3.

Basic engine oil testsStrategic Reliability Solutions

Basic engine oil testsStrategic Reliability Solutions

Viscosity (American Society for Testing and Materials D445) – The viscosity levels should ideally fall within ±5% of the original value. If they exceed ±10% of the original value, then the levels will fall out of the classification for that grade of oil.

For instance, Mobil Delvac 15w40’s kinematic viscosity, at 100°C, is 15.6 millimeters squared per second (mm2/s), according to its technical data sheet. If this value drops below 14.04 mm2/s or above 17.16 mm2/s then it can no longer be classed as a 15w40 oil and will not be able to properly lubricate the engine. These values vary depending on the manufacturer, application of the oil and the lab being used. These are a guideline in this example.

TBN – This is the amount of alkalinity remaining in the oil. The oil’s alkalinity helps neutralize the acids formed in a diesel engine. This value is always depleting as acids are continuously forming in an engine. However, if the TBN value drops below 40% to 50%, then there isn’t much reserve left to continue to protect the oil. This is the threshold limit, which can vary depending on the application, but this is a good guide to follow.

Additives – All finished lubricants have additive packages. These will vary depending on the oil producer. However, a few additives should be on your radar when trending their depletion in diesel engine oils. These include zinc, phosphorus, magnesium and calcium. These additives typically form parts of the dispersant, corrosion and antiwear additives that protect the oil. Ideally trending the decline of these may be helpful but your lab would have reference values (based on the type of oil) and can advise on concerning levels.

Wear metals – During the engine's lifetime, components will wear. Depending on the engine’s manufacturer, the warning limits will also vary (this also differs depending on the application). Iron, aluminum, chromium, copper, lead, molybdenum and tin are some metals to trend. If other special metals are in your engine, then you can ask your lab to include them in the oil analysis report. Typically, if there is an upward trend, this indicates wear/damage of specific components.

Operators can perform a simple test to determine if metal filings are in their oil (indicating some form of wear). They can place the oil in a shallow container and then place a magnet below the container or place the magnet in a sealed plastic bag and immerse it into the container. When the magnet is removed, if there are metal filings on the magnet, then this indicates the presence of wear metals, and the mechanic should begin investigating for damaged components.

Contaminants – These include any material which is foreign to the lubricant. Typically, labs test for the presence of sodium and silicon. Depending on the application’s environment, these values can increase indicating that they are entering the system somehow. Usually, this can occur during lubricant top-ups or improper storage and handling practices.

Presence of water – This is never a good sign because water can affect the lubricant by changing its overall viscosity, bleaching out some of the additives and even acting as a catalyst. Many labs perform a crackle test (where the oil is heated and if it produces a “pop” sound, then that confirms water in the lubricant. In certain instances, it is obvious that there is water present because it settles out in the sump/container. Labs can also perform a test to quantify the volume of water present. Typically, 2,000 ppm to 5,000 ppm is too much for most applications but this varies depending on the manufacturer.

Operators can perform their version of the crackle test by placing some of the oil in a metal spoon and heating it with a flame. If it produces a pop, then they can confirm that the oil has too much water in it before sending it off to the lab. Note: This should not be done in a highly flammable environment!

Fuel dilution – This occurs in most diesel engines due to the nature of the engine. However, limits need to be adhered to because too much fuel in the oil can lead to drastic changes in its viscosity. Usually, this value should not exceed 6%, but this can vary depending on the application and the manufacturer.

One way that operators can find out if there is fuel in their oil is to place a small drop of the oil on a coffee filter and leave it to “dry” for some time. The oil will spread out in concentric rings and if there is fuel present, there will be a rainbow ring. This means that the mechanics need to figure out if there is an issue with any of the injectors or seals in the diesel engine.

Ideally, the main idea with oil analysis is to develop a trend for your equipment and understand how the values align over time. This can help operators spot if an inaccurate sample was taken (possibly after a top-up, directly after an oil change or even from the bottom of the sump). An analysis also assists in planning the maintenance of components. For instance, if the value of iron in the oil analysis report keeps increasing then there is a strong possibility that some iron component is wearing. This can give the mechanic the time they need to investigate the engine and replace the component before it causes unscheduled downtime.

Protect One of Your Greatest Assets

Your diesel engine oil is one of the greatest assets in your fleet. You should be able to use an oil that aligns with your application while slowing its degradation rate with good practices and managing its health. Diesel engine oils form a critical part of your operation and deserve attention.

References

American Petroleum Institute. (November 18, 2016). New API Certified CK-4 and FA-4 Diesel Engine Oils are Available Beginning December 1. Retrieved from API: https://www.api.org/news-policy-and-issues/news/2016/11/18/new-api-certified-diesel-engine-oils-are

American Petroleum Institute. (February 19, 2024). API's Motor Oil Guide. Retrieved from API: https://www.api.org/-/media/files/certification/engine-oil-diesel/publications/motor%20oil%20guide%201020.pdf

The International Council on Combustion Engines. (2004). Guidelines for diesel engines lubrication - Oil Degradation | Number 22. CIMAC.